Brazil

The last great apes of the Atlantic Rainforest

While the focus of the world is on the Amazon disappearing, on the other side of Brazil another rainforest has almost completely disappeared; The Transatlantic Rainforest. Containing one of the most special forest dwellers on the entire planet and the last great apes of Latin-America; the Muriqui.

It is not easy to find the Feliciano Muriqui Reserve located in the mining state of Minais Gerais. The state is almost as big as France and is mainly known as farmland. Between all the big grazers, farms and coffee plantations there is a special place where time has stood still. Here is one of the last preserved pieces of Transatlantic rainforest. Of this primeval forest, only 7% of the original area is left in Brazil, while it once covered the southern part of Brazil with a lush green carpet of trees and plants. The Atlantic rainforest once stretched over the coast from the state of Salvador in eastern Brazil to the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul on the border with Uruguay. Stretching more than 3000 kilometers and more than 1 million square kilometers of rainforest, it was the size of neighboring Bolivia. The ecosystem of the Atlantic rainforest is also one of the most bio-diverse on earth, after the Amazon. Most of this rainforest was logged to make way for farms and mines, there are only some small pieces of forest left over from the primal Transatlantic Rainforest. And since these areas are not contiguous, it is difficult for many species to really thrive. In the 1980's only 50 muriqui were left in the park but because of conservation efforts there are now 350 to 400 northern muriqui in the park, out of a total of around 2000 muriqui (southern and northern subspecies) throughout Brazil. About 200 years ago, more than 1 million of these monkeys were swinging all across the continent, but luckily they were never completely extinct.Walking threw the dense, humid forest it is difficult to spot the muriqui. Luckily there are a lot of beautiful birds, macaques, howlermonkey's and even a tarantula crossing our path.

Parkranger Roberto Pereira is standing next to the forest, with his machete already in hand. The situation of the park appears to be dire and Pereira apologizes for the state it is in. “I worked together with two other rangers, but they left after the salary was no longer paid. The park is my birthplace so I stay here because my heart will break when I leave and somebody needs to protect the muriqui."

José Feliciano was the founder and patron of the park. "My father worked for Señor Feliciano and I was already walking behind them as a little boy. It used to be a reserve ánd farm where coffee was grown. Because of the fertile soil a lot of the forest was cut down, but luckily this piece of forest is left over. Señor Feliciano had to protect this reserve against other farmers, sometimes even with a gun in his hand. ” Pereira feels visibly proud when he talks with nostalgia about him and finds it a shame that little is being done today with the conservation of the park and the Transatlantic forest. And while new animal and plant species are still being discovered in the forest and more than 60% of the endangered species of Brazil live in the remaining Transatlantic rainforest. Pereira makes his way through the overgrown forest with his machete. After a bend he suddenly points to a tree on the edge of the forest and urges a finger on his mouth to be quiet.

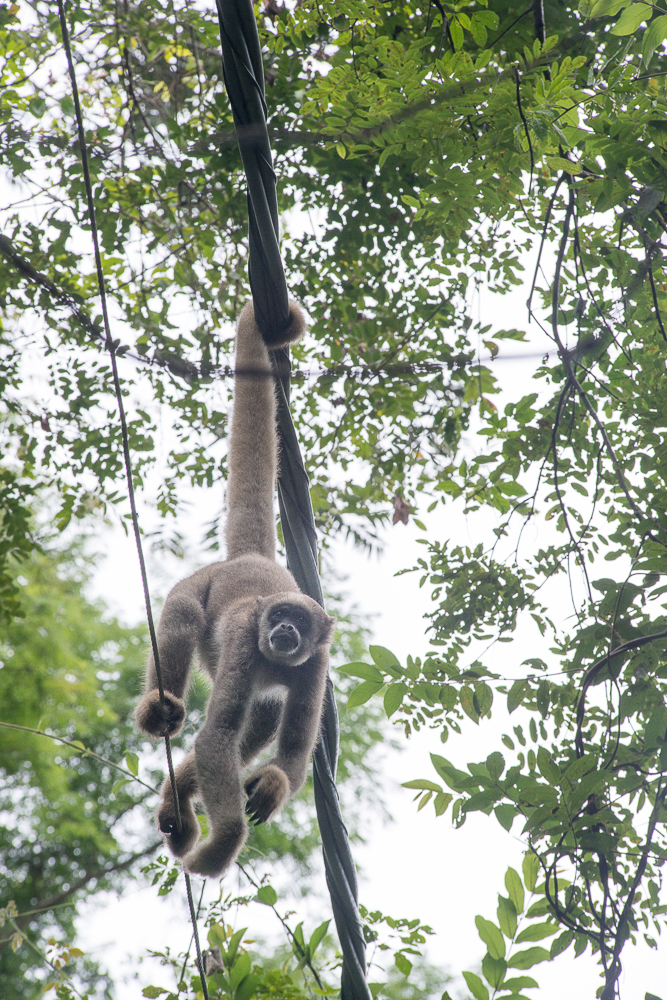

One by one they slowly descend from the forest-covered mountainside. They have a beautiful creamy-white fur and an endearingly soft face that looks very human. Moving like accomplished samba dancers, they go through the treetops and use their tails to move from one branch to the other. Then they quietly eat some berries or fresh flowers and then move on after the cries of the other group. According to one of the researchers who is also walking along, it is a well-known group of about thirty muriqui who travel to the other side of the park to forage through the trees and electric wires. We follow them for almost two hours while they eat, stretch or play with each other until they are too high in the treetops. Seeing these beautiful primates is a unique experience and the research team hopes that in the future more attention will be paid to these largest monkeys of Latin America, so that they will remain protected from extinction. Whether that also applies to the rest of the Transatlantic rainforest is not clear. Many of the coastal areas where the forest is located are also one of the most urban areas of Brazil, which means that more and more land is being claimed for buildings. Fortunately, in recent years less and less logging has been registered and there are NGOs that plant native trees. Such as SOS Mata Atlantica, who planned almost 1 million young trees around urban areas in 2018 so that there is more connection from the existing forest. Because not only the Muriqui depend on the Atlantic Rainforest but also the millions of people who inhabit the coastal areas of Brazil.